The events in December 1944

The history

Memory of invinsible soldiers of the Battle of the Bulge.

Invisible soldiers

Few realize that a decisive factor in the defense of Bastogne, during the Battle of the Bulge, rested in the artillery support of the surrounded town. One of the heavy (155mm) artillery units was the segregated 969th Field Artillery Battalion joined by a few howitzers and survivors of the segregated 333rd Field Artillery Battalion. For their actions the 969th FAB received the Presidential Unit Citation, the highest award a military unit can receive. In spite of this meritorious service, participation by Black G.I.’s in the Battle of the Bulge, or for that matter in the Second World War, is not well known or recognized.

Everyone knows of the Tuskegee Airmen and some know of the 761st Tank Battalion and the Red Ball Express. However, the majority of the Black G.I.s in World War II, 260,000 in the European Theatre of Operations, were not forgotten to history, they were simply never acknowledged. They are the ‘invisible” soldiers of World War II. They include eleven young artillerymen of the 333rd Field Artillery Battalion (FAB) who were murdered by the SS, after surrendering, during the Battle of the Bulge – the Wereth 11.

The 333rd Field Artillery Battalion

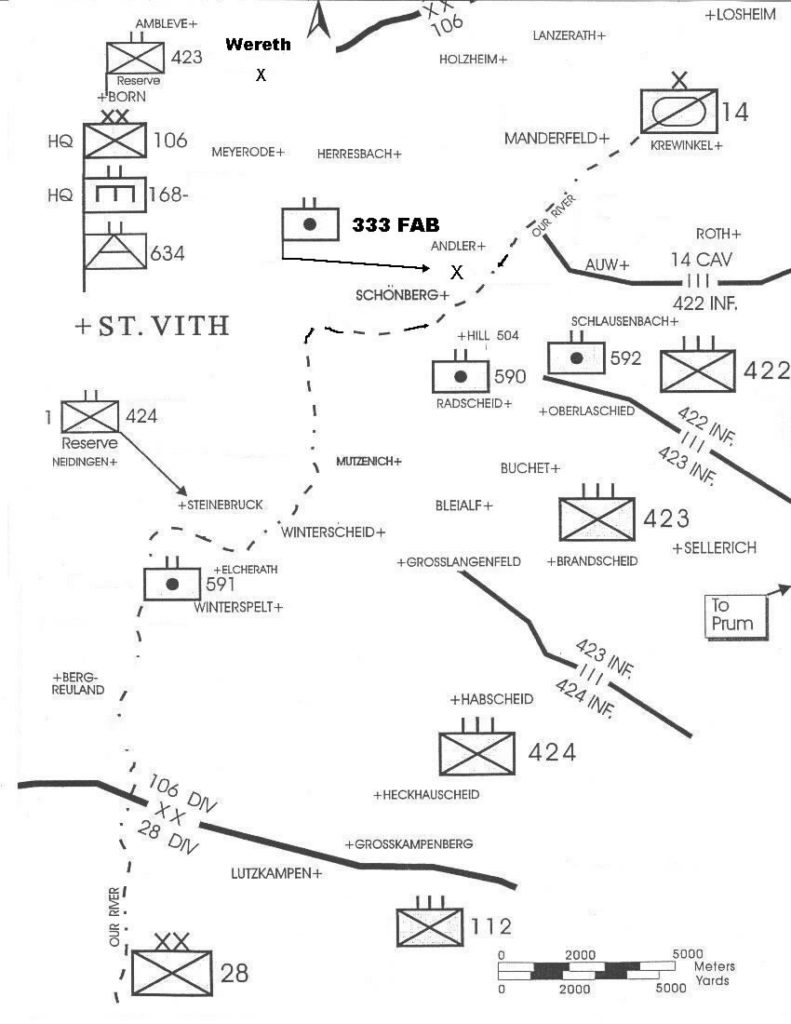

The 333rd Field Artillery Battalion was a 155mm Howitzer unit that had been in action since coming ashore at Utah Beach on June 29, 1944. Typical of most segregated units in World War II, it had white officers and black enlisted men. At the time of the Battle of the Bulge, the unit was located in the vicinity of St.Vith, Belgium. Specifically it was in the small village of Schonberg, having arrived there in October of 1944. The Service battery was west of the Our River, while the firing batteries (A, B, and C) were across the east side of the Our river in support of the Army VII Corps and especially the 106th Infantry Division.

In the early morning hours of December 16th, German artillery began shelling the Schonberg area. By the afternoon, with reports of rapid German infantry and armored progress, the 333rd FAB was ordered to displace further west but, at the request of the 106th Div. artillery commander, to leave ‘C’ Battery and Service Battery in position to support the 14th Cavalry and 106th Division.

Shelter for the eleven soldiers

By the morning of December 17th, the Germans were in Schonberg, and in control of the bridge across the river that led to St. Vith. Service Battery tried to displace to St. Vith through the village and were brought under heavy fire. Those not killed were forced to surrender. However eleven men of different Batteries who were caught on the east side of the river went overland in a northwest direction in the hopes of reaching American lines. At about 3 pm, they approached the first house in the nine-house hamlet of Wereth, Belgium, owned by Mathias Langer. A friend of the Langer’s was also present.

The men were cold, hungry, and exhausted after walking cross-country through the deep snow. They had two rifles between them. The family welcomed them and gave them food. But this small part of Belgium did not necessarily welcome Americans as “Liberators.” This area had been part of Germany before the First World War and many of its citizens still saw themselves as Germans and not Belgians. The people spoke German but had been forced to become Belgian citizens when their land was given to Belgium as part of the First World War repatriations. Unlike the rest of Belgium, many people in this area welcomed the Germans in 1940 and again in 1944, because of their strong ties to Germany. Mathias Langer was not one of these. At the time he took the Black Americans in he was hiding two Belgian deserters from the German Army and had sent a draft age son into hiding so the Nazis would not conscript him.

The massacre

About 4 PM, a four man German patrol of the 1st SS Division, belonging to Kampfgruppe Knittel (recent information shows these men to be from 3. SS-PzAA1 LSSAH). arrived in Wereth in their Schwimwagen vehicle. It is believed a Nazi sympathizer informed the SS that there were Americans at the Langer house. When the SS troops approached the house the eleven Americans surrendered quickly, without resistance. The Americans were made to sit on the road, in the cold, until dark. The Germans then marched them down the road. Gunfire was heard in the night. In the morning, villagers saw the bodies of the men in a ditch at the corner of a cow pasture. Because they were afraid that the Germans might return, they did not touch the dead soldiers. The snow covered the bodies and they remained entombed in the snow until January when villagers directed members of the 99th Div. I&R platoon to the site.

Hermann Langer, that time aged 12, was on his way home from church, and he immediately recognized the eleven soldiers, he had served food and drinks on 17 december. He never forgot this picture, just as the sentence of an American truck driver remained in his memory: “We collect the white bodies first”, leaving the bodies of the Wereth Eleven in the snow.

The bodies had been frozen and unmolested since the massacre The official report noted that the men had been brutalized, with broken legs, bayonet wounds to the head, and fingers cut off. It was apparent that one man was killed as he tried to bandage a comrade’s wounds. Prior to their removal an Army photographer took photographs of the bodies to document the brutality of the massacre.

“The murder of the Wereth 11 was seemingly forgotten and unavenged”

After the massacre

An investigation was immediately begun with a “secret” classification. Testimonies were taken of the 99th Div. men, the Army photographer, the Langers and the woman who had been present when the soldiers arrived. She testified that she told the SS the Americans had left! The case was then forwarded to a War Crimes Investigation unit. However the investigation showed that no positive identification of the murderers could be found (i.e. no unit patches, vehicle numbers, etc) only that they were from the 1st SS Panzer Division. By 1948 the “secret” classification was cancelled and the paperwork filed away. The murder of the Wereth 11 was seemingly forgotten and unavenged!

Seven of the men were buried in the American Cemetery at Henri-Chapelle, Belgium, and the other four were returned to their families for burial after the war ended. The Wereth 11 remained unknown, it seemed, to all but their families until 1994.

The memorial

Herman Langer, the son of Mathias Langer, who had given the men food and shelter, erected a small cross, with the names of the dead, in the corner of the pasture where they were murdered, as a private gesture from the Langer family on the fiftieth anniversary of their deaths.

But the memorial and the tiny hamlet of Wereth remained basically obscure. In a tiny hamlet with no school or shops, there were no signs on the roadways to indicate the memorial, and it was not listed in any guides or maps to the Battle of the Bulge battlefield. Even people looking for it had trouble finding it in the small German speaking community.

In 2001, three Belgium citizens embarked on the task of creating a fitting memorial to these men and additionally to honor all Black GI’s of World War II. With the help of an American physician in Mobile, Alabama, whose father fought and was captured in the Battle of the Bulge, a grassroots publicity and fund-raising endeavor was begun. The land was purchased and a fitting memorial was created.

There are now road signs indicating the location of the memorial, and the Belgium Tourist Bureau lists it in the 60th Anniversary “Battle of the Bulge” brochures. The dedication of the memorial was held in 2004 in an impressive military ceremony.

Further research on the men and their unit continues. Two families of the murdered men have been located, as well as three U.S. gravesites.

It is believed that this is the only memorial to Black G.I.s, and their units, of World War II in Europe. Our ongoing efforts are to improve the memorial site, educate the public to its’ presence and encourage black/segregated units of WW II to place unit plaques at the site. Our sincere hope is to make the memorial a focus of these units participation, and of American sacrifice during WW II.

Any contribution is greatly appreciated and goes entirely to the preservation of the memorial, there are no administrative costs. We encourage any unit to place a plaque at the site. Contact us for further information.

The goal is to make the Wereth 11 and all Black G.I.’s “visible” to all Americans and to history. They, like so many others, paid the ultimate price for our freedom.